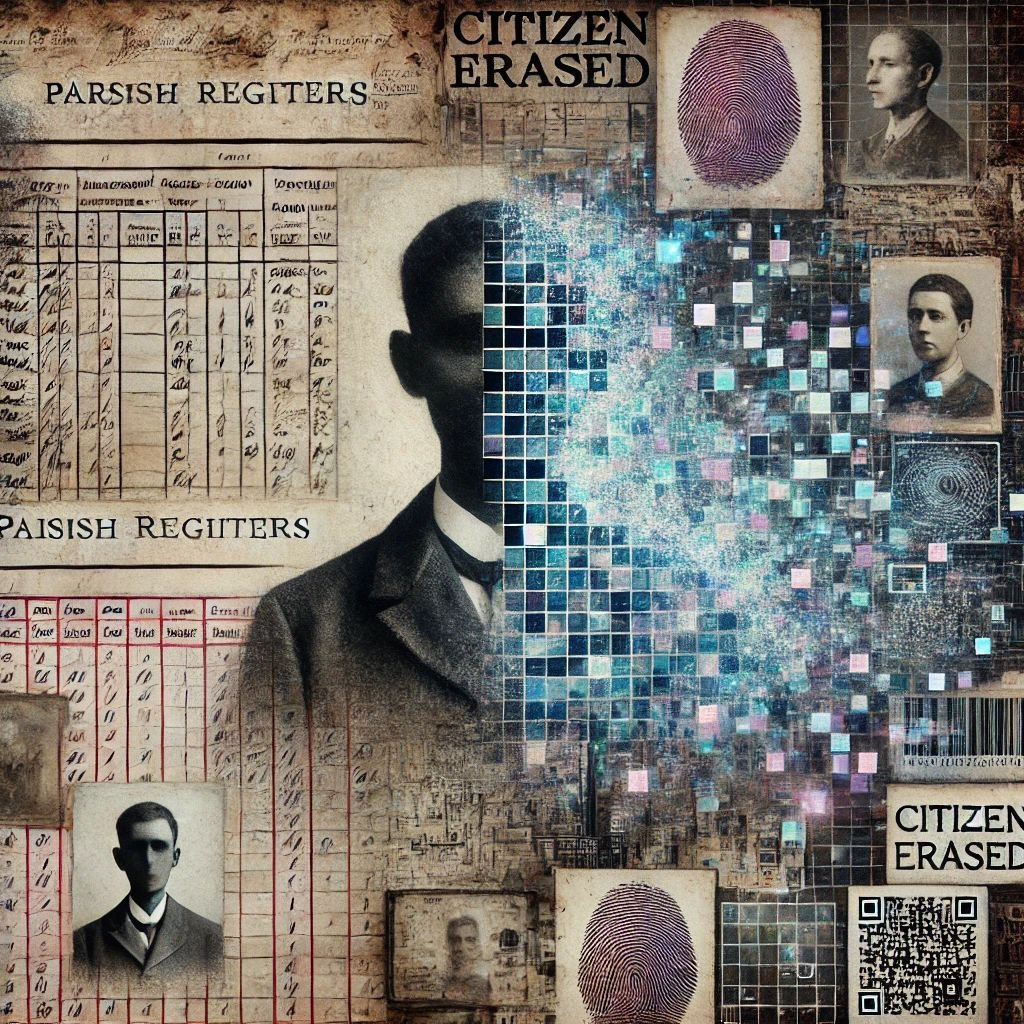

While documenting an ordinary family tree of renters, laborers, and forgotten ancestors, a pattern emerged: lives only recorded when the state or church needed them. This series follows that thread from parish registers to digital ID systems, revealing a continuity of population management—and asking what freedom looks like today.

Migration as Mechanism

When tracing family history, certain patterns begin to emerge. People weren’t just moving—they were being moved. Names shifted from rural parishes to fringe districts of London. From small towns in Hertfordshire and Buckinghamshire to addresses in Fulham, Acton, Hammersmith, and Shepherd’s Bush. Not upward. Outward. Inward. Then compressed.

There was no land to inherit, no estate to tend, no business to run. The only constant was movement—and behind that movement was something larger.

What looked like a migration of families was, in truth, part of a system: the urban throughput machine. A city built not to house individuals, but to channel, extract, and cycle labor.

This post is about how 19th-century cities like London weren’t accidental—they were constructed as infrastructure for managing people, turning human energy into wealth for those at the top, and transience into stability for the state.

What Is Throughput?

In systems thinking, throughput refers to the rate at which inputs pass through a system and are transformed into outputs.

In the industrial city, the input was people—bodies, hours, families, lives.

The outputs were:

- Rent

- Wages

- Taxes

- Commodities

- Control

Cities like London became machines for:

- Attracting labor

- Housing it minimally

- Circulating it efficiently

- Extracting value continuously

This system didn’t reward the worker with ownership. It rewarded the machine with motion.

From Rural Labor to Urban Volume

In our own family tree, the transition is stark:

- Skilled rural trades like chairmaking and millwork disappear by the 1850s

- Families are pulled toward London, settling in fringe suburbs undergoing rapid construction

- Housing types shift from cottages to rented terraces and subdivided flats

- Occupations shift to coachmen, carmen, domestic service, and gasworks labor

They weren’t seeking opportunity in a romantic sense—they were being absorbed into a growing system that needed them to exist, but not to rise.

They moved not to build—but to survive.

Who Designed the Machine?

Railway Companies

- Built transport lines directly into new suburbs to facilitate commuting and goods movement

- Purchased land cheap and sold it high after laying tracks

- Encouraged housing development by marketing “reachable” neighborhoods

Landowners & Speculative Builders

- Aristocratic families and early developers sold or leased plots for housing construction

- They had no obligation to build quality—just to extract rental income

- 99-year leaseholds ensured income now and asset reversion later

Employers and Industry

- Needed a stable, nearby labor force

- Supported zoning and infrastructure that would increase worker proximity to industrial sites

The State

- Introduced water, gas, sewerage, and police in response to population growth

- Collected data via census and tax rolls to manage density and prevent unrest

All of these actors worked together—intentionally or not—to turn London into a machine for throughput, not upward mobility.

Life Inside the System

Families arriving in London lived:

- In rented rooms, often sharing with extended family or lodgers

- Near rail lines, factories, or transport hubs

- With little chance of saving for property or investment

In the records, names appear at addresses that changed every 5–10 years. Parents died young. Children entered work early. Housing was dense, and often unfit.

Yet the rent kept flowing.

There are no wills, no land titles, no probate entries in these lines. Because the system wasn’t designed to accumulate wealth at the bottom—only at the top.

The Resource: The Working Body

Let’s be clear: the resource wasn’t land, goods, or even capital—it was people.

The machine ran on:

- Reproducible labor

- Disposable time

- Endless need

Every family that moved into the city was a resource node. Their labor was extracted through employment. Their earnings were funneled into rent and basic consumption. Their children refueled the cycle.

They weren’t serfs in the old feudal sense—they were participants in a managed flow.

And the more people came, the more stable the machine became.

Immigration: Sustaining the Flow

When local birth rates or working-class health couldn’t meet demand, the system turned outward.

London’s working districts were filled not just with internal migrants, but with:

- Irish families fleeing famine, absorbed into dock work and construction

- Jewish immigrants escaping pogroms, funneled into tailoring and trades

- Italian, German, and Chinese laborers entering service, transport, and laundry work

They were not welcomed—but they were needed.

And once they arrived, they entered the same throughput economy: low pay, high density, minimal rights, perpetual rent.

The Math of the Machine

Input: One family, renting two rooms in West London

Revenue Streams:

- Weekly rent to a landlord or leaseholder

- Wages spent locally on food and fuel (feeding other businesses)

- Taxation on goods, housing, and services

- Children who enter the labor force within 10–12 years

Cost to system: Minimal

Value extracted over 20 years: Substantial

Wealth accumulated by the family: Zero

Multiply that by hundreds of thousands of households, and you have the economic basis of the modern city.

Not Upward—Outward

Some families moved “up” in terms of housing quality or location—but they rarely achieved wealth.

Instead, their movement was lateral:

- From Fulham to Acton

- From rented room to rented house

- From one employer to the next

Any progress was reabsorbed by rising costs, inflation, or health crises. The system rewarded motion, not accumulation.

They were mobile—but never free.

Feedback Loops of Growth

The more people flowed into the city, the more:

- Landowners profited

- Investors collected returns

- The state extended its infrastructure

- Employers controlled labor supply

This feedback loop accelerated development:

- Rail led to housing

- Housing led to labor

- Labor led to taxes and consumption

- All of it led to consolidated ownership and rising inequality

Even as conditions improved slightly—more paved streets, more schools, more lights—the fundamentals didn’t change.

The system got smarter, not fairer.

In the family tree, what looked like movement was in fact containment.

The streets may have changed. The addresses updated. But the system stayed the same.

The industrial city wasn’t built for you to own—it was built for you to serve.

And as long as you stayed in motion, you could survive.

Ownership was at the edges. The center was throughput.

And the working class was its fuel.

Up Next: Immigration and the Maintenance of Throughput →

Discover more from Kango Anywhere

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.