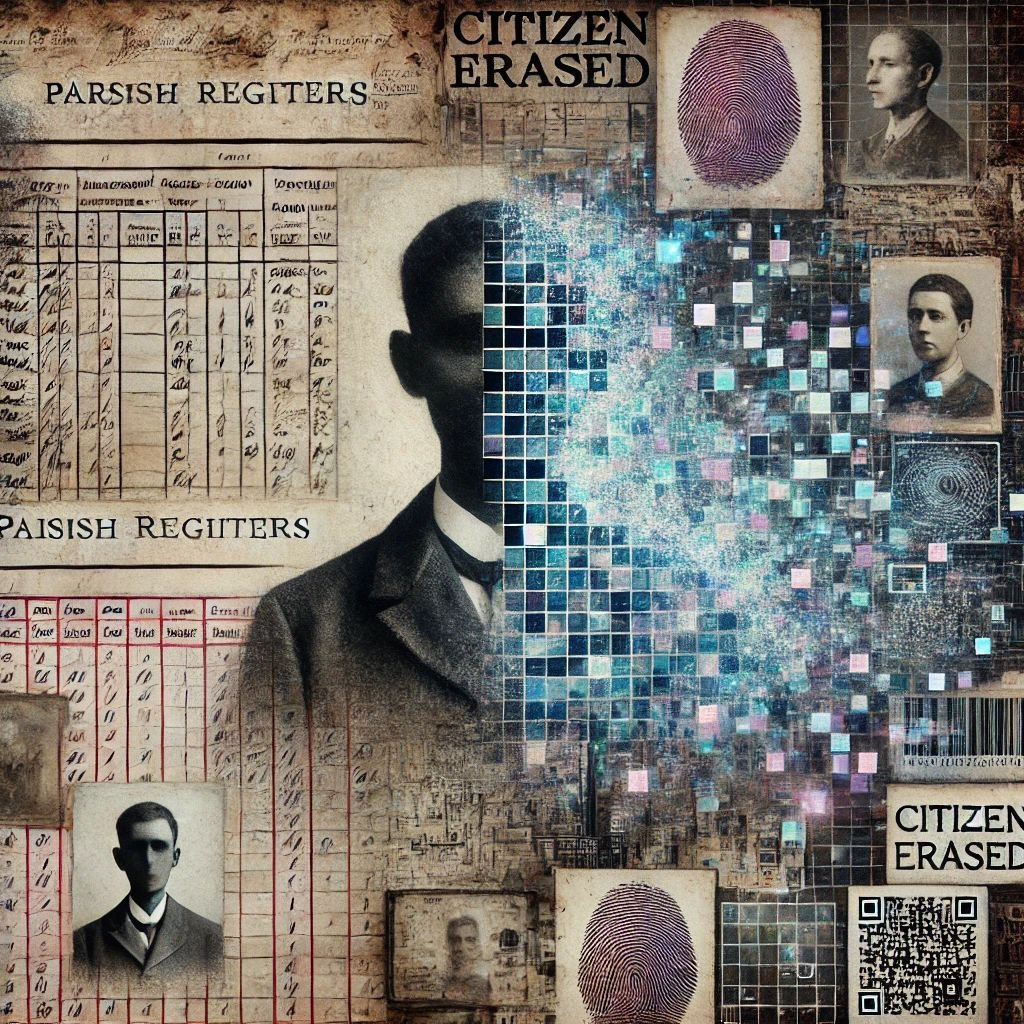

While documenting an ordinary family tree of renters, laborers, and forgotten ancestors, a pattern emerged: lives only recorded when the state or church needed them. This series follows that thread from parish registers to digital ID systems, revealing a continuity of population management—and asking what freedom looks like today.

Starting with a Family Tree

It started with a simple curiosity: how far back can I trace my family tree?

In this case, the tree traced back to rural Hertfordshire and Buckinghamshire, where chairmakers, coachmen, and mill laborers lived out hard-working, undocumented lives. By the mid-1800s, the branches shifted to Fulham, Hammersmith, and Acton—fringe-London areas that were quickly being swallowed by the city’s industrial sprawl. The names were ordinary. The stories were mostly absent.

And that absence became the story.

Because genealogy doesn’t just tell us where we come from—it tells us who got remembered, who disappeared, and who decided what was worth recording.

The Upper Class: Legacy in Ink

If your ancestors were aristocrats, landowners, or clergy, you’ll find:

- Heraldic visitations

- Wills and estate papers

- Parish plaques and monuments

- Family histories written and preserved intentionally

Their genealogies stretch back centuries, not because they lived longer or better—but because recordkeeping served them. Their existence was tied to property, power, and continuity.

They were remembered because their lineage mattered to the state and to each other.

The Working Class: Noted Only When Necessary

The rural laborers and urban poor in my tree left no journals or land deeds. Their names appear only in:

- Census counts every ten years

- Parish registers if baptized or buried

- Workhouse logs or criminal records

They weren’t remembered—they were recorded. A birth to be taxed. A death to be buried. A head to be counted.

Most of my family branches fade by the early 1800s. Before that, the trail ends—not because the people didn’t exist, but because nobody needed them to. The system had no reason to remember a wheelwright’s daughter or a chairmaker’s son unless they were paid, policed, or passed on.

Recordkeeping as Class Infrastructure

We tend to think of records as neutral, but they are not. They are tools of management. Throughout history, recordkeeping has always aligned with:

- Power

- Property

- Population control

A birth certificate isn’t just for family memory—it’s for citizenship, taxation, and inheritance. A census doesn’t preserve your identity—it ensures your household is known, mapped, and planned for.

Even the modern fascination with ancestry kits and DNA testing builds on the assumption that data is useful when monetized—whether by health companies, governments, or algorithms.

The Archive Is a Mirror of Class

The genealogical silence around working-class ancestors isn’t a fluke. It’s a structural pattern. It reveals that:

- Genealogy is stratified

- Recordkeeping is selective

- And visibility has always been a function of utility

Your family was remembered if the church or the crown could make use of them. Otherwise, they passed quietly, remembered only in stories—if even that.

What began as a family tree became a political map.

The names I found were important—not because they were powerful, but because their disappearance speaks volumes. They labored, migrated, married, raised children. But their stories were not curated. They were only stocktaken—counted like inventory.

That silence isn’t empty. It’s a clue. It tells us who history was written for—and who it forgot.

And that’s where this journey begins.

Up Next: Recordkeeping as Population Control →

Enjoyed this post? Follow the full series “From Family Tree to Global Grid” and subscribe to stay informed as we trace how recordkeeping, class, and digital identity are converging into a new form of control.

Discover more from Kango Anywhere

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.